NORTHERN IRELAND

Conflict Analysis with a peace perspective

WHERE? In which country/region is the conflict taking place?

Northern Ireland, Europe

WHO? Which parties are involved in the conflict?

The Northern Ireland conflict is an internal conflict between different groups and organisations which can generally be divided into two conflict parties. On the one hand, the predominantly Catholic Republicans/Nationalists, and on the other, the predominantly Protestant Unionists/Loyalists and the majority government which, until 2022, had been occupied by them.

WHEN? What are the key events in the conflict?

1919-1922: The war of independence, Irish-Catholic Nationalists versus the British-Protestant occupying power results in the division of the island and the establishment of a Protestant-controlled Northern Ireland.

1967: Formation of a Catholic/Nationalist civil rights movement against the discriminatory policies of the Protestant government. Demonstrations by civil rights activists meet with resistance from Protestant Unionists.

1969: Start of the civil war between the paramilitary “Irish Republican Army” (IRA) and the British army and Protestant/Unionist paramilitary groups.

10.04.1998: Signing of the Good Friday Agreement between the conflict parties leads to a cease-fire and the formal end of the civil war which claimed 3,600 fatalities.

Since 2016: Tensions due to Great Britain’s exit from the European Union (Brexit), and, to some extent, old lines of conflict, result in new riots. In 2019, a female journalist is shot dead by the New IRA in street disturbances. In the 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly election, for the first time a Republican/Nationalist party (Sinn Féin) won the most seats and thus the right to nominate a First minister.

HOW? What means are used in the conflict?

Paramilitary organisations were formed on both sides before and during the armed conflict. The IRA, on the side of the Catholic Republicans, carried out bombings and launched explosives, took hostages and carried out targeted shootings of police officers and British soldiers. On the side of the Protestant Unionists, paramilitary organisations such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) fought against the Republicans using similar means. There was a total of 16,200 attacks and 22,000 armed assaults, the victims of which were often civilians. The British army, sent in by Great Britain to de-escalate the situation, was, on the one hand, a target of IRA attacks. On the other hand, the British army used armed force against the IRA and the nationalist civil rights movement, for example, on “Bloody Sunday”, when British paratroopers shot dead 13 demonstrators. Great Britain and the British army tried to prevent street conflicts and acts of terrorism with mass detentions and the banning of rallies, andfinally, the dissolution of the Northern Ireland Parliament. A total of one in twenty people were injured during the civil war in Northern Ireland.

WHY? How can the conflict be explained?

Nationalism (cultural explanation)

For centuries before the division of Ireland, two different cultural identities had been developing on the island: on the one hand, the Irish Catholics and on the other, the British Protestants who had been settling in Ireland since the 12th century and finally colonised the island. After the division of Ireland, the long-held desire for Irish independence and a united Ireland without British influence intensified in the areas with a Catholic demographic. Thus, it was more a matter of national/cultural identity than religious allegiance, and the Irish Catholics even today feel that their national identity is threatened by the Protestant Unionists. On the other hand, the Protestant Unionists see their British identity endangered by the nationalist aspirations of the Catholic Republican demographic and maintain their insistence on the union of Northern Ireland with Great Britain.

Inequality and discrimination (power-based explanation)

Since 1922, the Irish-Catholic minority has been increasingly discriminated against and disadvantaged by the Protestant-controlled government and also the generally Protestant police force. This has led to the strengthening and radicalisation of nationalist aspirations on the part of Catholics/Republicans which has once again fuelled the fear of loss of influence and positions of power on the part of Great Britain and the Protestant Unionist demographic. Thus, in the Northern Ireland conflict, it is not merely a question of defending identity but also of relationships of dominance, sovereignty, political self-determination and power. Unequal access to the employment market and economic inequality are also considered to be significant causes of the conflict.

POTENTIAL FOR PEACE

Which peace initiatives have already been implemented?

The peace process initiated in the 1990s can, on the one hand, be attributed to movements within civil society, especially women’s movements, and also to the endeavours of political players led by the Irish and British governments.

In the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, the IRA and the other conflict parties agreed to end armed violence, to recognition of the other side and to a concordance democratic system which guarantees participation in legislative and governmental power to all conflict parties. The disarmament of paramilitary groups, the reforming of the police and the establishment of democratic structures has also been successful with the intervention of the Irish and British governments, an international commission and support from the EU, which has initiated and co-financed reconciliation programmes. However, the situation in Northern Ireland can still only be considered as a “cold peace”, in which, on the one hand, levels of violence have significantly decreased as a result of national and international engagement. On the other hand, the war is inadequately dealt with in society and consequently, old rifts between the conflicting parties still exist. These are manifested in outbreaks of violence, Protestant parades to commemorate historic victories over the Catholics, the hoisting of their own flag or the burning of the opposing side’s flag and the denominational division in education. The “Peace Walls”, walls which separate Protestant/Unionist areas of the city from

Catholic/Republican areas, are, on the one hand, part of the solution to curb violence and on the other, a symbol of the enduring potential for conflict.

What kind of approaches to peace are currently under discussion?

As the use of violence has, to a large extent, decreased, it is the numerous initiatives and organisations at grass roots level that, through their work, try to apply other approaches to peace and to break down the existing divisions in society. The focus is mainly on the themes of reconciliation, dialogue and education. Organisations such as the youth centre Forthspring Inter Community Group, the neighbourhood aid group South Belfast Partnership Board or the reconciliation centre Corrymeela have initiated various projects that create space for encounters and dialogue. Such projects range from educational programmes for children of both denominations about conflict counselling, political discussion between hostile groups to joint gardening projects. Churches and church organisations sometimes highlight the old lines of conflict, yet members of both denominations, through ecumenical services, educational work and voluntary service, are committed to overcoming the existing rifts. Other organisations are involved in trauma healing and in guaranteeing compliance with human rights in Northern Ireland. Former combatants are also engaged in youth work to raise the awareness of children and young people and to demonstrate the consequences of civil war. On a political level, discussions are taking place regarding compensation of victims of direct violence and also dealing with perpetrators. The Northern Ireland Protocol, which was intended to prevent stationary border controls between the two countries, has been designed to meet the challenge of Brexit and the risk of a hard border between Northern Ireland and the island of Ireland, (the latter is a member of the EU.) The conflict over the Northern Ireland Protocol between the EU and the British government which lasted for three years and fuelled concerns about a new escalation of old conflicts in Northern Ireland was settled by the Windsor Framework in Feb 2023.

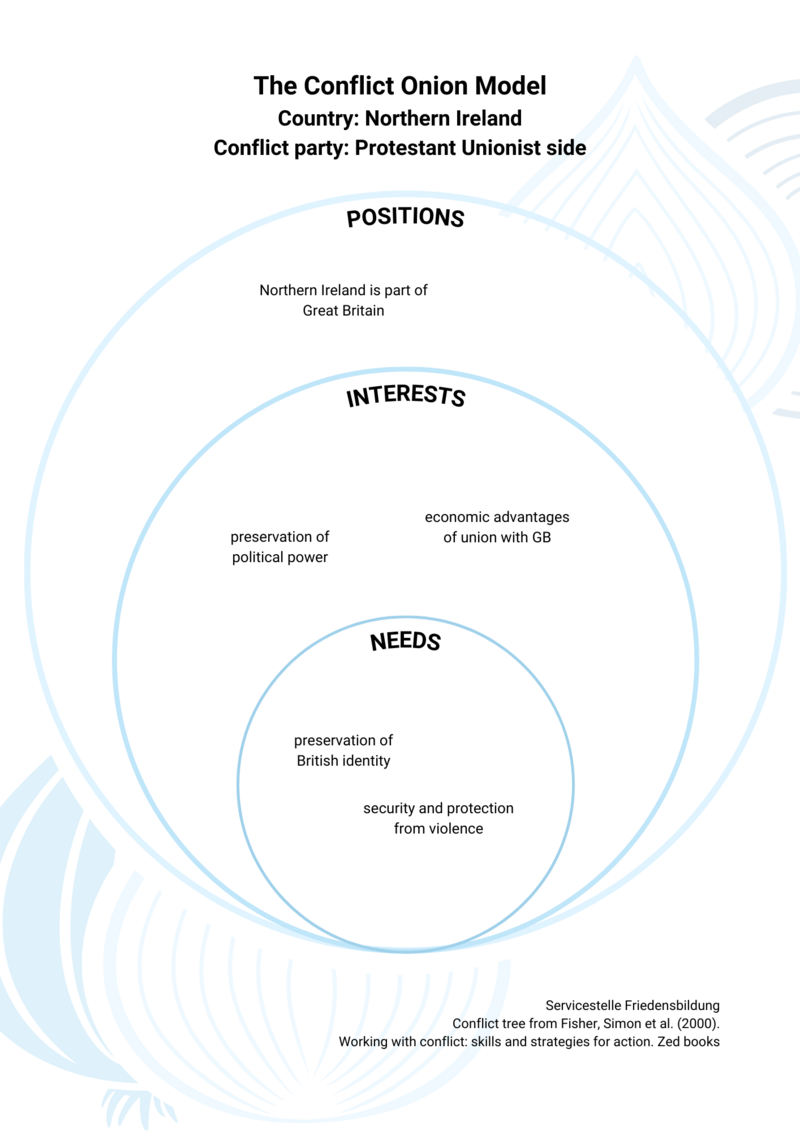

Conflict Onion Model

Conflict party: Protestant Unionist side

Positions

- Northern Ireland is part of Great Britain

Interests

- economic advantages of union with GB

- preservation of political power

Needs

- preservation of British identity

- security and protection from violence

Worksheet Conflict Onion (blank)

Worksheet Conflict Onion Northern Ireland Protestant Unionist Side (filled)

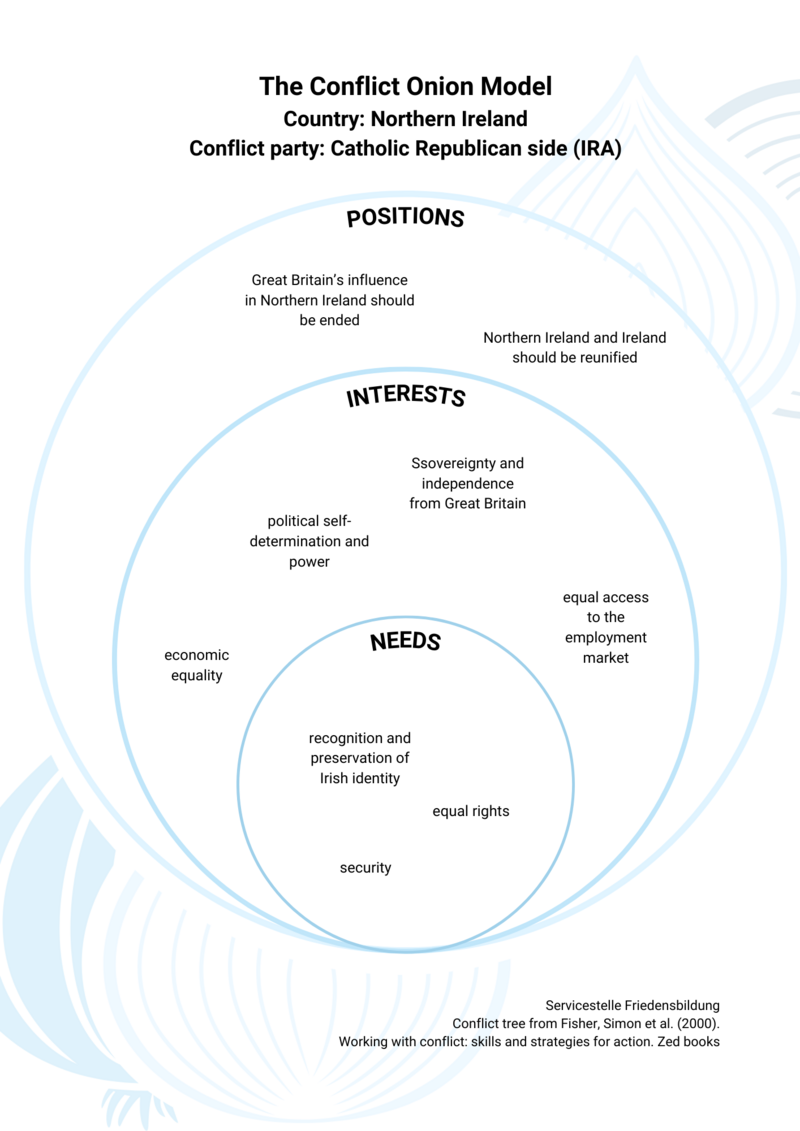

Conflict party: Catholic Republican side (IRA)

Positions

- Great Britain’s influence in Northern Ireland should be ended

- Northern Ireland and Ireland should be reunified

Interests

- sovereignty and independence of Great Britain

- political self-determination and power

- economic equality

- equal access to the employment market

Needs

- recognition and preservation of Irish identity

- equal rights

- security

Worksheet Conflict Onion (blank)

Worksheet Conflict Onion Northern Ireland Catholic Republican Side (filled)

Conflict tree

Effects

- spiral of violence

- hatred of the other side

- killing of civilians

- lack of trust even today

- decreasing willingness for dialogue and compromise

- "inherited“ trauma in families and communities

Core problem: conflicting understanding of national identity and sovereignty

Root causes of conflict

- colonisation of Ireland by Great Britain

- discriminatory laws

- imbalance of wealth and political involvement

- police reprisals

- nationalism

(vgl. Fisher et al., 2000: 29)

Sources

Sources

- Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (2020): Nordirland [Northern Ireland]

- Fenton, Shioban (2018): The Good Friday Agreement, London: Biteback Publishing.

- Fitzduff, Mary (2002): Beyond violence: Conflict Resolution Processes in Northern Ireland, UN University Press.

- Kandel, Johannes (2005): Der Nordirland-Konflikt. Von seinen historischen Wurzeln bis zur Gegenwart, [The Northern Ireland Conflict. From its historical roots to the present] Bonn: Dietz.

- Hancock, Landon (2014): Narratives of Identity in the Northern Irish Troubles, in: Peace & Change, Jg. 14, Nr. 4, S. 599-617.

- McKittrick, David; McVea, David (2002): Making Sense of the Troubles. A History of the Northern Ireland Conflict, London: Penguin.

- Moltmann, Bernhard (2005): Dem Frieden verschrieben – dem Konflikt verhaftet. Zur Rolle der Kirchen im nordirischen Friedensprozess [Committed to Peace – Arrested in Conflict. On the Role of the Churches in the Northern Ireland Peace Process], Frankfurt: Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung, Report Nr. 5/2005.

- Moltmann, Bernhard (2011): Friedensprozesse. Im Krieg mit dem Frieden beginnen. Das Beispiel von Nordirland [Peace Processes. Starting with Peace in War. The example of Northern Ireland], in: Berthold Meyer (Hrsg.), Konfliktregelung und Friedensstrategien, Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, S. 163-182.

- Moltmann, Bernhard (2017): Nordirland. Das Ende vom Lied? Der Friedensprozess und der Brexit [Northern Ireland. The End of the Song? The Peace Process and Brexit], Frankfurt: Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung, Report Nr. 4/2017.

Maps

- Karte 1: Karte Nordirland. The World Factbook 2021. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2021.

- Karte 2: Lagekarte Nordirland. The World Factbook 2021. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2021

- Karte 3: Bevölkerungszusammensetzung in Nordirland. Kartographie: mr-kartographie, Gotha Lizenz: Creative Commons by-nc-nd/3.0/de | Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung 2017

Further material:

- Berghof Foundation. Peace Counts: „Ex-Terroristen und kalter Frieden” (PDF)